Fort Ross Post Office (1877-1928)

By John E. Allen

It has been nearly a hundred years since Fort Ross had a post office. Between the years of 1877 through 1928, the Fort Ross community was served by an eponymous post office. During the 51 years the Fort Ross Post Office was in operation during the “Ranch Era,” it served a small farming, dairy and lumbering community with fewer than a hundred residents. The Fort Ross post office was just one of 5,808 post offices in operation in California between 1849 and 1990. Fort Ross had two postmasters: George Washington Call, and his son, Carlos A. Call, the last owners of the Fort Ross ranch. Each operated the post office consecutively; 1877-1907 and 1907-28.

Geography had conspired to make the northern coast of California one of the most difficult areas to access on the planet. Transportation and communication, even under the best of conditions, was limited to mountainous paths and a few poorly maintained roads, or by equally dangerous travel by ship along the rugged coast. All of these factors left Sonoma and the adjoining counties extremely isolated from the outside world. This would be especially the case when it came to establishing tenuous mail routes. The delivery of mail was challenging to say the least when it came to road washouts, downed trees and the occasional road agent.

Postal communications began in California with the first European settlement and the arrival of the Spanish in 1769. Letters were used as official correspondence between the twenty-one missions, four presidios and three pueblos that made up the Spanish borderlands and the outside world. Soon after, as other Europeans and Americans began to show up along the coasts, residents had other options for dispatching mail. Still, Californios had few easy means of communicating with the outside world; either sending mail by a long and hazardous overland route to Mexico or by the sporadic arrival of ships along the coast. With the first appearance of the Russians in 1806, Alta California was opened up for the first time to trans-Pacific communication networks that included Siberia – and by extension European-Russia, Alaska, and the Hawaiian Islands.

The earliest letters took the form of sheets of writing paper folded and sealed with wax wafers. The outside would be addressed and sometimes dated by the sender and often docketed by those that received them with date received and a summary of the letter’s contents. With the introduction of paper envelopes in the 1840s, sheets of various sized paper were inserted into the gummed envelopes designed to be sealed by moisture. In time these envelopes became known as “covers.”

Official manuscript cancellations noting dates and places of the correspondence’s origins are known for the Spanish and Mexican periods. Eventually, officially-produced handstamp cancellations were applied to outgoing mail from Alta California. The earliest known example of such an inked, stamped cancelation is from 1834 carried by a military carrier between Monterey and San Diego. No known handstamp cancelations from the Russian-American colonies are known to the author, but they could easily exist in Russian archives and other collections. Some idea of this extensive volume of mail, sent and received, can be gathered from publications by James R. Gibson, W. Michael Mathes, and Glenn J. Farris.

The first large-scale use of metal or wooden handstamps was introduced to California with the California Gold Rush in 1848. From two official US post offices in that year, the number of post offices grew to over 500 by the 1860s. In 1847, the first postage stamps were introduced by the U.S. Post Office, and postage stamps became mandatory in 1856. These handstamps were mandated by postal regulation to include the name of the town, but also the state and the date (and sometimes the year) the letter was received by the post office.

The use of stamps also meant the need for some form of cancellation to prevent their reuse. These took many different forms: pen-and-ink manuscript crossing marks on the porous surface of the stamp, or inked metal or wooden hand stamp impressions. Because the use of manuscript cancellations predates the opening of the Fort Ross post office in 1877, none probably ever existed.

Since manuscript cancellations were prohibited after 1860, new devices came into use as stamp obliterators or “killers.” They were often produced by the postmasters themselves from anything at hand; cork, wood or metal. Before becoming standardized, these often took on very unique and creative designs. A new type of uniform machine cancelation came into use at the turn of the 20th century with 4-Bar stamp obliterators for the stamps as part of the whole circular cancelation.

Postmasters were not furnished with handstamps from the Post Office until 1884. Prior to that time, only post offices that produced $300 in annual revenue received them automatically. This meant that many postmasters had to purchase their own at a cost of between $1.50 and $2.50 from various suppliers. At no time during its early years of operation did the Fort Ross post receive the needed amount to be automatically issued a handstamp. Early on, handstamps took various forms, circular (usually 29-33 mm), oval, or a multisided shapes. An examination of early Fort Ross covers reveals the use of some interesting shapes, sizes and letter fonts.

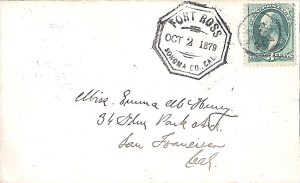

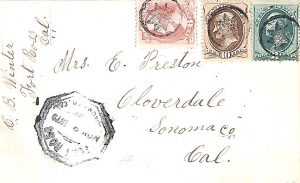

Below are two 1879 Fort Ross covers using the earliest known handstamps. The first cover has a fancy octagonal handstamp typical of the 1870s and 1880s that also lists Sonoma County. It is accompanied by an 8-pointed star in circle “killer.” It is the earliest known date for this type.

The second cover has 18 cents in stamps to cover the cost for registered mail. Registered mail required that each postmaster along the route had to personally take responsibility for the letter’s delivery by signing off on receipt of the letter, before forwarding it on to the next office. Registered mail was first introduced in 1855. The letter’s cost had to be paid in stamps after 1867 (initially including a 5-cent registry fee).

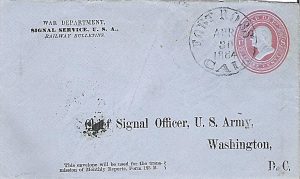

The next cover, dated April 30, 1884, tells us a particularly fascinating story concerning life Fort Ross. The official Signal Service cover below is of particular interest in that it points to a little-known part of Fort Ross’ ranch era history. The extra-large 31 mm cancelation with bold lettering is the only known example for this type.

The US Post Office began issuing stamped postal stationary envelopes in 1853 and official postal envelopes for government use in 1874. The pre-printed blue cover was used for official War Department correspondence. This particular cover most likely held a monthly climatological report made at Fort Ross in 1884 for the Signal Service. The Signal Service was established in 1870 as the weather observation section of the Army Signal Corps. Usually most periodic weather-related data was collected through the US Military Telegraph (USMT) system all across the American West. Locations that did not have access to the telegraph would have sent their collected data by the US Mail instead. George W. Call first began making voluntary weather observations in 1874. This proud tradition of sixty-four years of uninterrupted climatic measurement was carried on by his son Carlos and was acknowledged by the National Weather Service in 1972. This meteorological data, collected from throughout the West for over a century, continues to provide valuable information from today’s climatologists.

The next cover, with a 5-cent stamp addressed to Switzerland, provides us with evidence of the small community of Swiss-Italian dairymen that resided at the Fort Ross ranch.

An examination of the 1887 cover’s backside reveals not only the route, but time involved in transit. It first took the March 17 cover a week before reaching New York. After crossing the Atlantic, it finally reached Locarno on May 4, 1887.

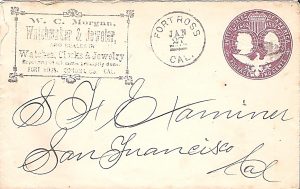

The following two covers are interesting because of the stamped corner card advertisement they each carry. The first carries a more standard sized handstamp and target “killer” and is dated July 11, 1894. It also has an incomplete corner card advertisement that has been incorrectly filled in by a former collector as part of attempted repair to “restore” the envelopment to its original state. If it was not for the following cover, we might be left to puzzle over watchmaker’s first name.

The second has a complete corner card that correctly lists the watchmaker’s name as W. C. Morgan. William “Uncle Billy” Morgan took on a number of roles at the Fort. He not only operated the Fort Ross Hotel and dance hall for George Call, but also helped at his store which housed the post office.

It makes use of the same handstamp, but with the year missing, and a crude cork killer cancelation. The lack of year date was probably due to the fact of Call not having the proper year slug to use in his handstamp. This handstamp is only known for the years 1893-94, so the reverse San Francisco cancelation for January 28, 1896, indicates that it was still in use a couple of years later. It should be noted that there are also two unique handstamp cancelations known for 1892 and 1900.

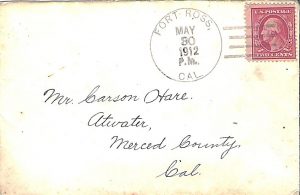

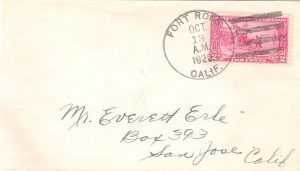

The Twentieth Century ushered in the use of more uniform and standardized handstamps (30-31 mm) which are accompanied by 4-bars. The last three covers are all examples with subtle variations of this distinctive type.

The above cancelation was in use between 1907 and 1913; and one below, between 1913 and 1924.

The next cover is of particular interest in that it represents a special class of covers created for stamp collectors. It is known as a “Last Day Cover” and as is often the case with these covers, they are not only dated on the last day of operation but are also signed by the postmaster/mistress. In this case, Carlos A. Call, son of the first postmaster and second and last operator of the Fort Ross Post Office. Prior to its final day of use on November 30, 1928, it had graced other envelopes for the previous three-years.

The reality of a declining population at the start of the 20th century and a change in postmasters in 1907 led to the closure of the Fort Ross Post Office. Mail service was first transferred to Duncan Mills, then to Cazadero and finally to Jenner, after the opening of the Pacific Coast Highway in 1925.

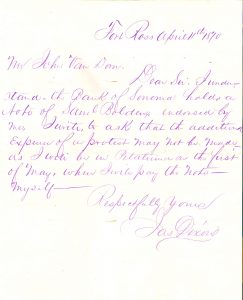

Unfortunately, as is often the case with some collections of postal history, the correspondence that was contained in the envelope was either separated or thrown away. Sadly, the accompanying letters are far fewer in many instances and have been lost to history. This holds just as true for Fort Ross too. Below is an 1870 manuscript letter from James Dixon, the previous owner of the Fort Ross ranch. A pencil notation on the reverse side reads “WF & Co – Duncan’s Mill” indicating that the letter was handled by Wells Fargo and Company and carried on one of express company’s stages.

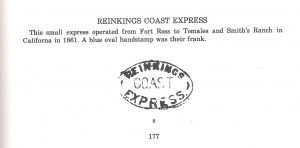

The role of contemporaneous private express companies on the Sonoma coast should also be noted. Two express companies were known to have operated in this remote region of the Golden State: Reinking’s Coastal Express and Wells Fargo and Company. Reinking’s operated between Fort Ross and Tomales Bay and Smith’s Ranch in the year 1861. At least one cover is known with the short-lived expressman’s handstamp. The letter originated in Bloom, Illinois on February 18, of 1861 and was routed through Bodega on March 28, before being delivered to the addressee, Norman Stuart, care of William Benitz. Wells Fargo and Company is listed as having opened an express office in 1886. To date, no known covers or cancelations have been identified for Fort Ross.

(From M. C. Nathan, Franks of Western Expresses, 1973)

On August 3, 1875, one of Wells Fargo’s stages fell victim to the notorious road agent, Charles E. Boles, aka Black Bart, along a lonely stretch of road near Fort Ross. The passenger-less coach was held up for $300 dollars in gold and a sack full of U.S. Mail. Later the empty postal bag was found with a short piece of doggerel that would make the versifying bandit famous:

“I’ve labored long and hard for bread,

For honor and for riches,

But on my corns too long you’ve tread,

You fine haired sons of bitches.

Black Bart, the Po8”

The lone, gentlemanly bandit would go on to rob a total of 29 stages before finally being arrested eight years later.

The Fort Ross ranch’s isolation proved to be a constant challenge. Until 1862 when Samuel Duncan opened his post office near his mill, it took an eighteen-hour trip to pick up the mail in Sonoma. After George Call’s failed attempt to build a road to Jenner in 1877, he then constructed a “mud wagon” road to Sea View. From there, a stage made its way to Guerneville, the terminus of the North Pacific Coast Railroad. By 1886, the line was extended to Cazadero, allowing for the mail to then proceed to San Francisco by rail and ferry.

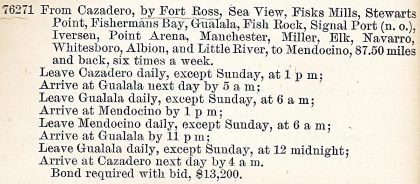

We learn something of how the Fort Ross office was interwoven into the network which linked other offices in the coastal area from the U.S. Advertisement of September 15, 1893, Inviting Proposals for Carrying the Mails of the United States in California and Alaska. An official U.S. Mail Route, number 76271, which ran six days a week with 87-mile round trips between Cazadero and Mendocino, was let out to bid in 1898 for $13,200 per year (see below). After the mailman left Cazadero at 1 P.M. he made his first stop at Fort Ross post office before then traveling onto Sea View and up the coast before reversing the order going in the other direction on the following day.

(from U.S. Advertisement of September 15, 1893, Inviting Proposals for Carrying the Mails of the United States in California and Alaska…)

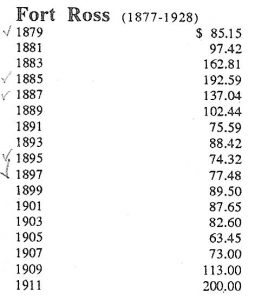

Much can also be learned from the U.S. Postmaster General’s Official Register which lists the compensation that was due each postmaster every two years, provided the post office took in less than $1,000. The odd-year listings between 1877 and 1911, show that the Fort Ross Post Office had more active years than others; with the years 1883, 1885 and 1911 being the busiest and the years 1895, 1897 and 1907 being the least so. Such information can help to indicate changes for more prosperous times or larger populations than census records ever decade.

(Fort Ross compensation listings from Alan Patera, California Postmaster Compensation, 1994)

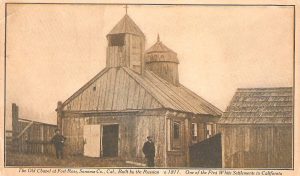

Finally, another facet that is closely linked with the postal history of the Fort Ross Post Office is the beginning of tourism in the 19th century and the advent of the post card. Officially issued government postcards came into use in 1873, while privately produced postcards for sale to the public became common in the later part of the century. These earliest cards were commercially mass printed, often in a stunning array of colors through the process of chromolithography. Until March 1, 1907, any messages had to be written in margins on the side carrying the image and the opposite side was reserved only for the address and stamp as in the example below.

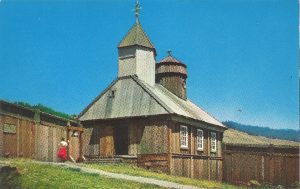

After 1907, the reverse field of the card was equally divided into spaces for a short message on the left and a space for the address and stamp on the right, such as this 1912 postcard.

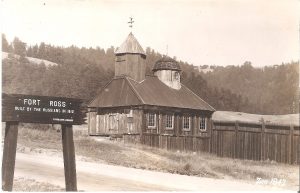

The first decades of the 20th century saw the golden age of what are called “Real Photo” postcards. Pre-prepared photographic paper was sold in postcard formats by a variety of companies to be used by amateur and professional photographers alike. After the photographic images were taken and later developed, they could then be sent as more personalized cards. Because of the nature of this process, far fewer “Real Photo” post cards were created than the massed produced printed ones.

Some of these post cards like the 1930s one above, when expanded, can actually help us in showing the location of the Fort Ross general store and post office location just outside the southwestern gate. After the closure of the post office in 1928, the building continued to serve the community as a store. In 1963, it was moved to its current location a short distance away to the north along Highway 1.

Other cards from the 1920s through the 1950s, like those below, can provide us with a series of views which document the various periods and changes made to the fort after it became a State Park. Many of these post cards were signed by the photographers, which include names like RHEA. Zan, Peck Photo and Lake Photo among others.

And lastly, some more recent postcards, though historically inaccurate, are just fun – like the Violet E. Alton “Flags Flown Over the California” series from the 1950s showing various historic California flags.

While the Fort Ross Post Office has not been in operation for nearly a century, it can still be hoped that many more generations of visitors will continue to purchase postcards of the fort and write, “Wish you were here.”

Short Bibliography:

John Boessenecker.Shotguns and Stagecoaches: The Brave Men Who Rode for Wells Fargo in the Wild West. 2018.

James L. Coburn.Letters of Gold: California Postal History Through 1869. 1984.

Glenn. J. Farris.So Far from Home: Russians in Early California. 2012.

Ernest Finley.History of Sonoma County, California. 1937.

Fort Ross Interpretive Association.The Caretakers of Fort Ross After the Russian-American Company. 1995.

J. P. Munro-Fraser.History of Sonoma County. 1880.

Walter N. Frickstad.A Century of California Post Offices. 1955.

James R. Gibson et al.Russian California, 1806-1860: A History in Documents. 2014.

Historical Atlas Map of Sonoma County, California. 1877.

Lyn Kalani and Sarah Sweedler.Fort Ross and the Sonoma Coast. 2004.

John F. Leutzinger.The Handstamps of Wells, Fargo & Co.: 1852-to 1895. 1993.

W. Michael Mathes. The Russian-Mexican Frontier: Mexican Documents Regarding the Russian Establishments in California, 1808-1842. 2008.

M. C. Nathan.Franks of Western Expresses. 1973.

Richard Paul Papp.Bear Flag Country, Legacy of the Revolt: A History of the Towns and Post Offices of Sonoma County California. 1996.

Alan Patera.California Postmaster Compensation. 1994.

H. E. Salley.History of California Post Office, 1849-1990. 1991.

Robert A. Thompson.Historical and Descriptive Sketch of Sonoma County, California. 1877.

Scott 2020 Specialized Catalogue of United States Stamps and Covers. 2019.

U.S. Advertisement of September 15, 1893, Inviting Proposals for Carrying the Mails of the United States in California and Alaska, from July 1, 1894, to June 30, 1898, W.S. Bissell, Postmaster-General.1893.

John H. Williams.California Town Postmarks, 1849-1935. 1997.

Neill C, Wilson.Treasure Express: Epic Days of the Wells Fargo. 1936.

Ernst A. Wiltsee.Pioneer Miner and the Pack Mule Express. 1931.

John E. Allen is a professor of history and a researcher for California State Parks as well as a former board member of the Fort Ross Interpretative Association (FRIA) in the 1990s.