JULY 2020 ENEWS

Dear friends of Salt Point and Fort Ross,

Dear friends of Salt Point and Fort Ross,

Time is misbehaving of late, made worse by all of us working from home, staring wide-eyed at our laptops for hours on end. I’m truly finding it difficult to accept that July is drawing to a close. Historically July is a physical & hands-on month for FRC staff as we prepare for Fort Ross Festival - we bustle about booking performers, Tim competently fixing canopies and tents, Sarjan renting many many things and maintaining a brilliantly balanced budget, Song ordering kvass & negotiating beer donations, and Melissa graciously organizing our immensely talented and generous 300+ volunteers to help us put on our annual summer party. Alas, not this year!

Let us all hope that on the last Saturday of July 2021 we are all together, making baskets and butter shoulder to shoulder, learning from our Kashia and Alaska Native friends, tasting borscht and taking in the sounds of Kitka, Kedry, Slavyanka. And the bells.

In other losses it’s also unlikely that many of our school groups will be coming to the park in September. To mitigate this, FRC is working on creating “distance learning” online versions of our Environmental Living and Marine Ecology programs to bring a little of Fort Ross and Salt Point into the classroom. I’m not so sure you can virtually replicate the “place” in an outdoor education setting but we are giving it our best in this era of flexible thinking. Plus we have one of the most photogenic parks to work with!

While school groups and large gatherings are not allowed, the good news is Fort Ross and Salt Point park grounds, trails, and beaches are open. Fortunately camping at Salt Point also just opened up. Unfortunately as of last week due to county-wide regulations the Visitor Center and bookshop at Fort Ross were mandated to close but we hope to get clearance to open them up soon. These details change weekly; see www.fortross.org for updates, or call us at 707-847-3437 Monday through Thursday to speak to Sarjan who is loyally holding down the fort.

The most important thing is the land itself: the park grounds and our lovely Sonoma coast are open and ready to receive you. I suggest you spend copious amounts of time outdoors in fresh air, surrounded by nature in all its forms, momentarily oblivious of today’s front page news.

Be well, be safe,

Sarah Sweedler

Fort Ross Conservancy CEO

Summertime and the Viewin’s in 3D

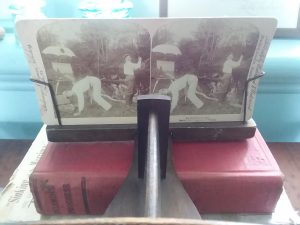

While summertime migrations aren’t that common among our friends in the animal kingdom, human migration in the summer is quite common. Well at least migrating to the air-conditioned theaters to cool off and enjoy the latest blockbuster movie. Alas, the COVID-19 pandemic has been quite the game changer, and a day at the movies is probably not in the cards this summer. Nevertheless, you may be able to make your own visual fun at home with a little inspiration from a Fort Ross Ranch era toy: the stereoscope.

A walk through the old 1870s Call Family residence at Fort Ross State Historic Park reveals technology of a simpler time, a time when people made their own entertainment right at home. Whether it was sitting on the porch and watching the comings and goings on (old) Highway One, making music on the fancy square grand piano, or peering through the stereoscope to watch photographs transform like magic from a 2D to a 3D image, coming up with ways to entertain oneself at home used to be the norm.

I’m not going to try to convince anyone that staring at a single, stationary 3D image will provide the same visual stimulation that a modern 3D movie spectacle offers. However, one of the nifty things about older technological devices, like the stereoscope, is that their simplicity makes their inner workings more accessible, and therefore creates enriching opportunities for hand-on educational pastimes that we don’t get from modern technology and toys, such as streaming tv, playing video games or an evening at the movies.

What is a stereoscope? According to Britannica Kids, it’s “[a]n optical instrument…[that] enables a person to view two-dimensional images so that they appear to exist in three-dimensional space.” Stereoscopes are simple vie

wing machines that are used to look at two images of the same subject taken from slightly different angles. When the left and right eyes view each separate image, the brain combines the two images together and perceives them as a single image with depth, creating a visual 3D experience.

British physicist Charles Wheatstone is credited with the invention of the stereoscope in 1832. Since then many different versions of the same basic device have been created. The one that lives in the Call Family home (now a public museum) is from the 1930s, according to the museum inventory. While the museum is currently closed to protect everyone’s health and safety, you can make your very own stereoscope at home for a fun art and science project fit for the whole family.

Check out these links for step-by-step instructions on how to make your own stereoscope and stereoscopic images with just a few easy-to-find, inexpensive supplies, and let the at-home entertainment begin!: Pixie Hill Paper Stereoscope project by Nichola Battilana, WikiHow: Make a Stereoscope, and Makezine: Make Your Own Stereoscopic Viewer.

While 21st century 3D entertainment is currently off limits, we can use this time of slowing down to go back to basics, and have some educational fun making our own old-fashioned 3D toys. And perhaps when the time comes that we can safely step out for a night at the theater, the experience will be that much richer since we’ve explored earlier technology that paved the way for our modern 3D movies. And don’t forget there are many dimensions to the fun that can be had at Fort Ross and Salt Point State Parks. Come on down to your favorite coastal parks and try your hand at taking some stereoscopic images for deep memories that will last a lifetime. We hope to see you in 3D this summer!

References & Recommendations:

- Call House Virtual Tour with Lynn Rudy

- The Fort Ross Ranch Era

- Britannica Kids: Stereoscope

- Wikipedia: Stereoscope

- Pixie Hill Paper Stereoscope project by Nichola Battilana

- WikiHow: Make a Stereoscope

- Makezine: Make Your Own Stereoscopic Viewer

--Charon Vilnai, Programs Instructor, Sea Lion Survey Project Lead, and Call House Museum Lead

Making Memories with Summer Blackberries

Deep summer in California means temperatures soar and, as a consequence, we seek cool places, cold drinks and sweet summer fruit to fight the heat. These long, hot days usually have us longing to spend time with friends and family at beaches, rivers, parks, or in our backyards, but Covid-19 has interrupted normal summer routines. How can we still celebrate this season, safely, by creating positive memories to look back on in years to come? By partaking in the age-old summer tradition of blackberry picking! There are two types of people: those who have gone berry picking and those who want to. If you’ve been, you probably have fond recollections of fingers, tongues, and lips stained deep purple, the pigment a testament to the deliciousness of these sweet summer fruits. You likely also recall scratches on exposed skin showing your dedication and sacrifice to reach the top-most clump of berries.

While there is a native blackberry species in California, the Pacific Blackberry (Rubus ursinus), which according to the California Native Plant Society “is one of the original parents of the hybrids Loganberry and Boysenberry,” it is generally the Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus Focke) we are all familiar with. The name Himalayan is misleading as the blackberry is in fact native to Armenia, hence its scientific name.

While there is a native blackberry species in California, the Pacific Blackberry (Rubus ursinus), which according to the California Native Plant Society “is one of the original parents of the hybrids Loganberry and Boysenberry,” it is generally the Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus Focke) we are all familiar with. The name Himalayan is misleading as the blackberry is in fact native to Armenia, hence its scientific name.

R. armeniacus made its way to California through our local celebrity, botanist, horticulturist, and “pioneer in agricultural science” Luther Burbank. He reportedly traded for the seeds somewhere in India, bringing them back to California in 1885. He named the berry the Himalayan Giant. According to NPRs “Food for Thought” by Ann Dornfeld, “In 1894, he offered the berry in a special circular he sent buyers in mild climates. It was popular.” Although Burbank endeavored to breed a thornless blackberry that he believed would revolutionize the public’s opinion of the fruit, it was in fact birds that made this berry ubiquitous throughout the U.S.. By 1945, it had naturalized along the entire West Coast.

The California climate turns out to be an ideal habitat for R. armeniacus, maybe too ideal. They thrive in riparian zones and wetlands. Seeds are dispersed in these waterways as well as by animals and birds. Dense thickets of vines are known to completely consume huge swaths of land. They love disturbed areas such as roadsides and livestock pastures, but have been seen growing in nearly every habitat from the Canada border to Mexico. These thickets make it impossible for native species to grow and can become a considerable fire danger. According to the California Invasive Species Council, “Mechanical removal or burning may be the most effective ways of removing mature plants...Reestablishment of Himalayan blackberry may be prevented by planting fast-growing shrubs or trees, since the species is usually intolerant of shade. Regrowth has also been controlled by grazing sheep and goats in areas where mature plants have been removed.”

Depending on each subclimate, Blackberries start to ripen in July and continue through September. When planning a berry picking adventure, remember to research the lands you’re planning to explore. Are they private, State, Federal? Depending on the property you may or may not be able to pick there. It’s advisable to cover all your limbs as the thorns of R. armeniacus are formidable and can do significant damage. Wear closed-toed shoes (not only because of the thorns) because berry brambles offer a wonderfully protective habitat for small ground rodents, and snakes take advantage of that -- during the hot summer months of July and August rattlesnakes can be a threat we need to consider when berry picking.

Bring a big bucket and a smaller bucket (like a yogurt container) with a string through the sides, this way you can have both hands free with the smaller bucket around your neck. The real trick is getting those berries in the bucket and not only to your mouth!

Recipes-

- American Heritage Cooking - Blackberry Buckle

- The Old Farmer’s Almanac - Blackberry Jam without Pectin

References-

- California Invasive Plant Council - Himalayan Blackberry

- California Native Plant Society - Pacific Blackberry

- Bay Nature - “How the Mistakenly Named ‘Himalayan’ Blackberry Became a California Summer Tradition”

- NPR “The Strange, Twisted Story Behind Seattle's Blackberries” by Ann Dornfeld

Photo Credits-

Rubus ursinus - Franco Folini

All other photos - Song Hunter

-- Song Hunter , Director of Programs

‘Point d'appui’: American Report to Congress on Fort Ross

The Russian American Company representing imperial interest in the New World was not the only 19th-century geopolitical player who was interested in claiming the Pacific Northwest and the strategic San Francisco Bay. The US and Great Britain were also eager to claim the fertile land that opened trade with China and the rest of the Asian markets. The sole power challenging Spain's and later Mexico’s claim to the territory was the small settlement of Fort Ross built by the Russians on the Sonoma Coast in 1812, just north of San Francisco, to hunt marine mammals and to supply produce to the Russian American outposts in Alaska. By the mid-1830s the United States became a serious contender to claim the Pacific Coast from California to Oregon, just as RAC made its final push to gain international recognition of Fort Ross. While ultimately both Russian and American attempts to claim parts of California for their respective capitals in the 1830s failed, Washington did observe the strategic importance of Fort Ross as a potential adversary to US national interest in the region.

Until Mexico proclaimed its independence from Spain in 1821, Alta California was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, ruled by Viceroy of New Spain. New Spain comprised what is now Mexico plus a large portion of the current United States, including California. Russia claimed the rights to the Pacific Northwest through the 1799 Imperial Decree establishing the Russian-American Company’s monopoly, as well as numerous explorations undertaken by Russians along the Pacific coast. In 1821, Czar Alexander I renewed RAC’s monopolistic privileges after signing a decree proclaiming sovereignty over North America at 45°50′ N latitude. The American and British authorities were quick to challenge the declared Russian borders, claiming that those lands have been explored by London and Washington long before the Russians arrived on the North American shores. After years of extensive negotiations between the three powers, St. Petersburg signed separate accords with Washington (1824) and London (1825) fixing Russia’s southernmost boundary at 54°40′N, with trading rights extending south of that latitude. The Fort Ross question was left untouched.

Spanish recognition of Russian claims in North America was more problematic. The Napoleonic Wars in Europe and its devastating effects on the Russian economy, as well as Tsar Alexander I’s post-war personal ambitions to preserve the power of monarchy across Europe and in the New World, had sidelined RAC’s decades-old aim to claim part of California for St. Petersburg. Spain and later Mexico refused to acknowledge Russia despite a legitimate treaty signed by Russian representative Captain Leonty Hagemeister with local tribal chiefs for possession of property near Fortress Ross in 1817. Both Spain and Mexico repeatedly approached Russian authorities demanding to dissolve Fort Ross. In the mid-1820s there were voices within the Company advocating the creation of a Russian buffer zone between the newly formed Mexican nation and the United States.

“In the matter of the occupation of land in New Albion everything depended upon ourselves and that if at times there were attempts by Spain, Mexico, and the Californian authorities to lay some sort of claim to our settlement in that region, then they arose solely from our own uncertain actions, which attested our doubt in our own rights,” Dmitry Zavalishin, a prominent Russian revolutionary, wrote after visiting California in 1823-24 aboard the Kreiser.

“It gradually became clearer and clearer that even the occupation of the Slavyanka River [ Russian River] would not suffice if we stopped there... we willingly or unwillingly satisfied ourselves that expansion would be truly significant only in the event that the boundaries that I proposed in 1824 were accepted, namely, to the north the boundary of the United States of America, recognized as the 42nd parallel of north latitude, to the south San Francisco Bay, and to the east the Sacramento River, which flowed into San Francisco Bay and which at that time was reckoned to flow from Lake Tumpanogos [Lake Tulares]. The late Count N. S. Mordvinov [***Count Nikolay Semyonovich Mordvinov was one of the most reputable Russian political thinkers of Alexander I's reign] even marked this boundary in his own hand on a map that I had given to him and that showed a further expansion at a later time to the east as far as the Rocky Mountains.” [see Gibson and Istomin, 2014, Vol I. pg 15]

This ambitious plan was never to materialize and the claims to Fort Ross were left unanswered all the way up to the sale of the fort in 1841. Unable to secure the Imperial support to seize part of California, in the mid-1830s, the Russian American Company had tried to enter negotiations with Mexico to gain concessions from the new nation. In 1834 RAC was making plans to send the governor of North American colonies Ferdinand von Wrangel to try to “legally secure the RAC’s territory in California in an expanded form.”

The US could not just sit idly and was making its own plans to expand its land boundaries.

The American expansion as a nation began with the Louisiana Purchase from France which added nearly 830,000 square miles to the country in 1803 for just $15 million. Next, the US purchased Florida from Spain for $5 million after the signing of the Adams–Onís Treaty in 1819, which also established the boundary of US territory and claims through the Rocky Mountains and west to the Pacific Ocean. In 1835, the US was willing to pay $500,000 [see Robert Glass Cleland, Jul 1914, Pg. 14] to Mexico to take over San Francisco Bay.

So while Wrangel went to Mexico in 1836 to negotiate the fate of Fort Ross, the Americans sent a scouting expedition under the command of William A. Slacum to access the state of affairs on the Pacific Coast. During the expedition, Scalum visited "Presidia Ross” in February 1837 to spy on the outpost, after “the presence of the Russians in California began to excite comment in the United States and to receive a certain amount of official attention.”

“In 1812 [Governor of Russian American Company Alexander] Baranov, the ‘Little Czar,’ succeeded in establishing a colony, to which he gave the name of Ross...Baranov had the more important purpose of ultimately extending the Czar's control over a large part of Upper California by means of this colony, and especially of seizing the Bay of San Francisco,” Slacum said in his report to the Senate that same year.

The surveyor recorded about 400 people living at the settlement at the time that comprised around 60 Russians and 80 Alaska Natives, in addition to apparently hundreds of California Natives living and working in the vicinity of the fort. All this manpower could be used to protect the outpost.

“The fort is an enclosure 100 yards square, picketed with timber 8 inches thick by 18 feet high, mounts four 12-lb. carronades on each angle, and four 6-lb. brass howitzers fronting the principal gate; has two octangular block-houses, with loopholes for musketry, and eight buildings within the enclosure and 48 outside,” Slacum recorded, just after Wrangel’s trip to Mexico in 1836 failed because of Nicholas I’s unwillingness to grant Mexico diplomatic recognition for the sake of Ross.

Slacum’s report on the fort, including its man power and firepower, were presented to American lawmakers as a force to be reckoned with. After assessing the state of Russian manufacturing, farming and trade at Ross, Slacum concluded that “this establishment of the Russians seems now to be kept up principally as a ‘point d'appui [***In military theory, ‘point d'appui is a location where troops are assembled prior to a battle] and hereafter it may be urged in furtherance of the claims of the ‘Imperial Autocrat’ to this country, has now been in possession of Ross and ‘Bodega’ for 24 years, without molestation.”

For more information please refer to the following sources:

William A Slacum, Memorial of William A. Slacum : Praying Compensation for His Services in Obtaining Information in Relation to the Settlements on the Oregon River, December 18, 1837 https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/100258113

Robert Glass Cleland, The Early Sentiment for the Annexation of California: An Account of the Growth of American Interest in California, 1835-1846, The Southwestern Historical Quarterly , Jul., 1914, Vol. 18, No. 1

Gibson James R. (Editor, Translator), Istomin Alexei A. (Editor), Russian California 1806-1860: A History in Documents, Vol II, Hakluyt Society, 2014

-- Igor Polishchuk , Director of External Relations