JUNE 2021 ENEWS

.jpg) Dear friends of Fort Ross and Salt Point,

Dear friends of Fort Ross and Salt Point,

Welcome, summer! We’ve been very busy at the park with plenty of tour requests, a bustling museum, and a surprisingly crowded parking lot both mid week and on weekends. I get the feeling we are all tired of living in our kitchen baking sourdough and we want nothing more than to explore other places and eat in other people’s kitchens. Everything feels a bit novel and new.

For us, today we gathered the Fort Ross Conservancy team for a staff meeting, our first in-person gathering in sixteen months. The pandemic saw all our school groups, events, and tours canceled such that the FRC team had their working hours reduced and almost everyone (save our dedicated bookshop crew!) worked remotely this past year. I’m grateful to the team for staying positive and adapting to what was a very difficult year. Today was a treat to meet in person, enjoy a picnic together, and begin to visualize a more normal summer and fall season.

And while we aren’t holding Fort Ross Festival next month, we do have some dates to share:

- October 16th, 2021: Harvest Festival

- December 11th: Fort Ross Conservancy Holiday Party

- May 2022: Reef Campground slated to reopen

- July 30, 2022: Fort Ross Festival (long overdue, so next year’s event will be a big one!)

We’ve got some great articles in this month’s newsletter I encourage you to read. And I wish you a pleasant summer season of exploration and novelty.

Happy trails,

- Sarah

Sarah Sweedler

Fort Ross Conservancy CEO

sarahs@fortross.org

Salt Point Camp Hosts Needed

Please help us spread the word!

We are looking for two camphosts to work at Salt Point in Western Sonoma County. We have immediate openings at both Woodside campground and Gerstle Cove campground.

The camp host provides information to the visiting public, reports emergencies and other park related problems to 911 or the ranger staff (law enforcement), assists our park aides, sells firewood, and updates camper reservation cards. The camp host needs to be friendly and diplomatic, possess good communication skills, and be competent at collecting and accounting for firewood sales, making change, and performing simple accounting procedures. A valid driver's license is required if you wish to use State Parks vehicles (rather than walking) to complete the campground patrols needed to update camper reservation cards.

The camp host reports to the State Parks campground Ranger. Camp hosts will be trained by DPR staff in campground operations.

The camp host must be willing to work weekends and holidays. The schedule for this position is 5 days on with either M/T or W/Th off. Applicants must be willing to commit to at least a 3 months which depending on need/desire to work longer could be extended an additional 3 months. An RV is required. In return for these services you may live without charge in your own RV in one of the most beautiful parks along the Pacific Ocean. There are full hookups at each camp host site. Gerstle Cove Campground is located about 1 hour north of Bodega Bay and offers 29 campsites and a group campsite. Woodside campground is located about 1 hour north of Bodega Bay and offers (up to) 78 campsites.

Please email Trevor.Nealy@parks.ca.gov or call (707) 875-3483 for further information.

You can find the camp host volunteer application at https://www.parks.ca.gov/?page_id=911.

Yellow Bush Lupine: Native and Invasive?

Walking down the bend of gravel road to merge with old Highway One at Fort Ross State Historic Park, a honeyed aroma reaches your nostrils. Following your nose, you take a right turn through the swinging wooden gate heading out into the cow pastures north of Fort Ross Cove. The source of the delightful scent becomes immediately apparent as your path opens up to the huge expanse of ocean terrace carpeted with silver-gray bushes covered with pale yellow flowers. You’ve discovered a field of Yellow Bush or Coastal Bush lupine (Lupinus arboreus) that’s filling the air with an incredible perfume like sweet peas in summer.

Yellow Bush lupine (lupin), while a true California native, comes with some controversy. The exact native range is unclear, but it’s thought that it originates south of Marin county, from Point Reyes National Seashore south to San Luis Obispo County.

Yellow Bush lupine does very well in poor soil and its roots are excellent at stabilizing eroding soils. It was widely introduced to Northern California,in the early to mid 1900s, particularly around the San Francisco Bay to stabilize shifting coastal dunes and bluffs. These days, Yellow Bush lupine grows from the river mouth of the Ventura River in southern California northward all the way to British Columbia.

Not only was it intentionally planted, but it spreads easily by seed. Because of this, the California Invasive Plant Council has declared the Yellow Bush lupine invasive outside its native range. As it spreads, it pushes out native species and often makes what we now have at Fort Ross - a monoculture.

To make matters more complicated, Yellow Bush lupine hybridizes with other native lupines. In fact, you can see examples of this right out on the bluffs of Fort Ross. Yellow bush lupine is also referred to as Tree lupine due to the fact that it often grows up to two meters tall. When on the hunt for the hybrid, look for a dwarfed plant, maybe 2 feet tall, with flowers of pale yellow and pale blue/purple. They tend to alternate colors up the flower spike.

Historically, the root fibers of the regionally native lupine species were used to make string nets. As mentioned in the Ethnographic Notes on the Southwestern Pomo by E.W. Gifford:

This flowering plant grows commonly along the coast. The fibers from its roots are used for string, which is called sulemA [sulema? "any string or rope" ]. String made from sinew is called ima [9ima"sinew" ]. Milkweed was not used for string by the South-western Pomo. The lupine roots were dug with a digging stick or an elk antler... Lupine bowstring [was] also used. It was almost as strong as sinew.

According to Jennie Goodrich and Claudia Lawson, the yellow flowers of the visually similar Lupinus luteolus Kellogg were “used in wreaths for the Flower Dance performed at the Strawberry Festival in May.” (American Indian Studies Center, University of California, Los Angeles, page 65).

True, the field of flowers is stunning, particularly right now, but these plants continue to present problems as they crowd native species out and change the pH of the soil with their pea-family nitrogen-fixing roots. California State Parks environmental scientists attempt to limit the spread of the population at Fort Ross using an integrated pest management strategy to control Lupinus arboreus. They have treated it with chainsaws to reduce biomass, herbicide to treat resprouts, and have hand pulled seedlings. They are hoping to treat it again this calendar year. Removal of the Yellow Bush lupine is a regular volunteer opportunity for students during our Marine Ecology Programs and if you’re interested, you can help us too during one of our invasive species removal days!

--Song Hunter, Distance Learning Programs Manager

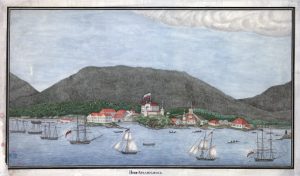

Porto Franco - Forgotten dream of free trade zone in California

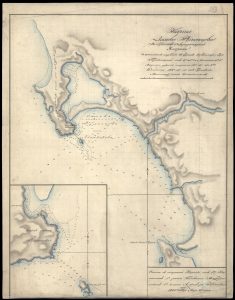

In 1837, the Russian American Company tried to transform Bodega harbor into the first free trade zone in the Pacific Northwest - a revolutionary idea for the time that aimed not only to reshape the economy of Fort Ross, but of the entire Alta California.

Mercantilism and protectionist policies, characterized by high tariffs and other barriers to trade with other nations, dominated the economic landscape in early Californian colonial history. The creation of a Californian Porto Franco, or a free trade port, envisioned a drastic shift from centuries-old economic practices by allowing the embarkment to receive and store imported goods free of customs duties before reexport. Free ports are created specifically to attract investment, promote trade, boost domestic manufacturing activity and employment which the Russian American Company thought would turn Sonoma Coast into a commercial hub with Fort Ross at its helm.

In November 1837, Russia’s Imperial Ministry of Finance started examining a proposal submitted by a “foreigner” Ludwig Bauer, which called for the establishment of a free trade port at Bodega Bay, which the Russians referred to as Port Rumyantsev. Very little is known about Ludwig Bauer. According to the Russian American Company papers, he was a merchant from Hamburg, Germany who spent several years trading in Mexico. He came to St. Petersburg from Berlin in 1837 intending to locate a harbor in Alta California from which to conduct trade with Mexico. He argued that such a free trade port would be advantageous to the Company desperately trying to make the Californian colony a profitable economic enterprise.

“Although the harbor of Ross is not one of the best, bad anchorages in Mexico, the West Indies, and South America nevertheless handle considerable trade. Large ships can anchor safely a half-mile from Ross, as well as draw much nearer,” the report from the Department of Manufacturing and Internal Trade to Minister of Finance Egor Kankrin about the ‘Project of Ludwig Bauer for the Development of the Colony of Ross’ read. “But its chief merit is its geographical location; it can be a trading depot for the Northern Hemisphere, just as Valparaíso is for the Southern Hemisphere and Callao is for the Equator.”

In addition to creating a free trade port, Bauer’s proposal called for a “colonization by German artisans and farmers” who would take over agriculture and manufacturing sectors at the Russian possessions. The introduction of Russian-German minorities to California, the Company thought, would not only benefit trade, but would also solve the labor shortages in its agricultural segment which has increased in Russian California with the establishment of three Ranchos - Chernykh, near present-day Graton; Khlebnikov, a mile north of the present-day town of Bodega, and Kostromitinov where the Pacific Ocean meets the Russian River.

Construction of a gunpowder factory at Bodega, Bauer’s proposal argued, would also benefit the Company, as this commodity was in great demand in Mexico, which was expanding its mining industry.

In 1838, after a review by the Ministry of Finance, the Russian American Company permitted Ludwig Bauer to establish a free trade port at Bodega, which would allow “merchant vessels of those nations that are not hostile to Russia” to enter the port “without any payment for anchorage (jaugeage et tonnage).”

Bauer and all persons “constituting his mercantile, manufacturing, and agricultural establishments,” as well as their children, were granted exemption from taxes, while Mr. Bauer was granted the “exclusive privilege of trade with foreigners at the port of Rumyantsev as long as the Company possesses this port.” The idea was indeed visionary for 19th century standards. In comparison, it would take the US government nearly 100 years to create its first foreign-trade zones in 1934 during the Great Depression to encourage international trade while promoting domestic investment.

What happened to Bauer remains a mystery to this day. Despite being granted permission to revolutionize trade practices in California, the German merchant never arrived in Bodega to transform the Russian harbor. Perhaps the fate of Russian California would have turned out differently if Bauer’s project was to succeed. The immigration of Russian-German minorities to the Great Plains after the American Civil War, for instance, had a massive successful impact on agriculture; for example the so-called ‘Volga Germans’ introduced Russian wheat varieties that soon became mainstays on the Great Plains. Perhaps, if the Russian-Germans settled in California, the Sonoma coast could have become the granary for Alaskan colonies the Company had always hoped Fort Ross would become.

After Bauer’s ambitions did not materialize, the Russians sold their Californian possessions to Swiss-born John Sutter, who paid $30,000 to acquire many of the materials and implements that went into the construction and development of Sutter’s Fort at New Helvetia (Sacramento). The discovery of gold at Sutter’s Mill in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada mountains in 1848 would soon transform the entire Californian economy. But that is a completely different story.

-- Igor Polishchuk, Director of External Relations

Those of us living around Fort Ross may have noticed an uptick in furry neighbors lately--bears! A Sonoma County resident living across from Fort Ross School had her very first encounter recently when a bear wandered right through her backyard this spring. “It wasn’t threatening,” she recounted, “just looking around.” After climbing up on top of the picnic table, it waddled off into the forest.

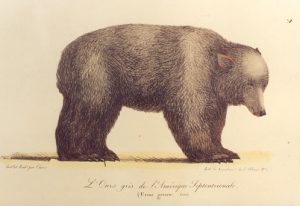

Nowadays, the bears occasionally seen around Fort Ross are black bears, which can grow up to six feet long and weigh around two hundred pounds. Historically, and certainly during the Russian era, the area was dominated by a more ferocious kind of bear: the California Grizzly. These shaggy brown bears could weigh up to 2,200 pounds, had claws up to four inches long, and could stand nearly ten feet tall on their hind legs.

Despite their ferocity, some indigenous groups along the California coast chose not to hunt bears and coexisted peacefully with them for thousands of years. According to California Indians and Their Environment by Kashia elder Otis Parrish and UC Berkeley Anthropologist Kent Lightfoot, the Miwok, for example, avoided bear meat because the animal’s feet looked too human. The Kashaya Pomo of Metini hunted bears frequently and particularly enjoyed the taste of the cubs, which they would dry or broil. Other indigenous groups along the California coast hunted bears with dogs or by smoking out their dens while the bears were hibernating.

During the 1817 round-the-world voyage of the Russian sloop Kamchatka, Fleet Captain Vasily Golovnin wrote dismissively of the Fort Ross area’s local grizzlies, saying that “all of the bears are brown and consequently have no value at all, but in New Albion near Trinidad Bay there are many black bears whose fur is very valuable.”

Despite the lesser value of their fur, by the early 20th century the California Grizzly Bear was hunted to extinction. The last confirmed California Grizzly sighting was in 1922, after years of conflict with ranchers and the popularity of “bear-baiting” spectacles, in which a captured bear was made to fight a bull. Midshipman Fyodor Litke, also on the Kamchatka, wrote of Pablo Vicente de Solá, the last Spanish colonial governor of Alta California, unsuccessfully attempting to catch a live bear for one of these events:

He intended to occupy us after dinner with the spectacle of a fight between a bear and a bull; for this he had already sent hunters to the woods several days ago to catch a live bear, but unfortunately (as he said) they did [not] succeed in this, and right after dinner, which had lasted much longer than we wished, we set off to the ship.

Before they were hunted to local extinction, the large and aggressive grizzlies dominated nearly every ecological niche, leaving the much smaller and more timid black bears to more inland territories. But while the only place you can find a California Grizzly today is on the state flag, black bears have been slowly moving into historic grizzly territories along the Sonoma coast. In fact, without competition from their bigger and meaner cousins, black bear populations today are higher than they have ever been.

Locals and officials around Fort Ross have taken notice of this uptick in bear encounters. In fact, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife estimates that black bear populations in the state have more than doubled in recent years, from 10,00-15,000 to 30,000-40,000.

The North Bay Bear Collaborative, a program launched by the Sonoma Ecology Center, is currently looking to capture the increasing demographics through a new research project. To get in contact, you can visit their webpage here.

-- Zez Wyatt, Special Correspondent

Visit Fort Ross and Salt Point - Book a Private Tour Today!

It’s a great time to visit Western Sonoma coast - the hills are still green, the wildflowers persist, and while this season can be a bit windy, we are seeing migrating humpbacks and plenty of marine mammals.

FRC offers private and group tours at both Fort Ross and Salt Point. Both of these locations are rich in human stories and natural history, and starting your visit with a private or group tour can help you more deeply understand the landscape and history.

The Fort Ross museum and bookshop are open seven days a week.