MAY 2021 ENEWS

Dear friends of Fort Ross and Salt Point,

Dear friends of Fort Ross and Salt Point,

This month’s newsletter focuses on what’s under foot, with articles on manganese mining near Fort Ross and a salty article about how Salt Point got its name. But before we dig deep into the landscape, let me first thank you for supporting our fundraiser.

What a pleasure it is to have such a supportive community! We’ve concluded our Fort Ross Education Fund fundraiser and thanks to you all, it was a big success -- we brought in just under $25,000!

This funding will allow us to offer our Marine Ecology and Environmental Living programming to more students at low or no cost. These programs help kids connect to the world around them and encourage them to see the continuum between the past and the present.

We are particularly grateful to Fort Ross Ventures, a global VC firm based in Silicon Valley, for their generous $15,000. donation.

If you know a teacher or homeschooler or any group wanting to bring students to Fort Ross for a full day or even an overnight, or to take advantage of our online virtual one hour classes, please reach out to us at info@fortross.org. For groups showing need we can offer partial or full subsidies. Please help spread the word.

This week we welcomed students from three classrooms back to Fort Ross -- our first onsite visits in over a year! -- and our instructors gave seven interactive online classes. We are sharing the Fort Ross Metini story with students from all around the U.S. and across the globe. This is what we love, and what we do well. Thank you to all who donated.

Wishing you a lovely Memorial Day weekend doing all the things we are now allowed to do in our mostly-vaccinated communities -- I’m thinking hugs, picnics & gatherings, restaurants …. and more!

Sincerely,

Sarah

Sarah Sweedler

Fort Ross Conservancy CEO

sarahs@fortross.org

Visiting Fort Ross and Salt Point - Book a Private Tour Today!

It’s a great time to visit Western Sonoma coast - the hills are still green, the wildflowers persist, and while this season can be a bit windy, we are seeing migrating humpbacks and plenty of marine mammals.

FRC offers private and group tours at both Fort Ross and Salt Point. Both of these locations are rich in human stories and natural history, and starting your visit with a private or group tour can help you more deeply understand the landscape and history.

The Fort Ross museum and bookshop are open seven days a week.

Fort Ross’ Manganese Extraction War Effort

Eighty years ago the Allied powers joined forces to defeat Nazi Germany in World War II. The Lend-Lease Act of March 1941 established an unprecedented level of collaboration between the Big Three Allied powers -- the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and the United States -- which allowed the coalition to sustain the joint war effort against Nazi Germany by exchanging military equipment, food, oil, and raw materials between partners.

Lesser known is how Fort Ross’s geology also played a role in helping the Allies defeat Nazism by providing manganese ore to the US government, which was experiencing a deficit of this strategic mineral supply.

Manganese

Manganese is a gray-white mineral with a pinkish tinge that is essential in metallurgy because of its ability to strengthen steel. The mineral’s essential uses in different civilian and military industries, combined with its lack of substantial ore deposits in the United States, forced Washington to import large quantities of manganese from abroad. One of the leading countries to supply the US with this critical mineral throughout much of the 20th century was Russia. During the war, Moscow was instrumental in replenishing Washington’s manganese stockpile by providing 32,000 tons through the ‘Reverse Lend-lease’ program.

In 1939 the government passed the Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act which allowed intensifying the acquisition of certain “strategic and critical” minerals for industrial, military, and naval needs, in which the “natural resources of the United States were deficient.” The legislature also encouraged developing mines and deposits of these materials within the United States. Manganese-buying depots were established to enhance domestic production, which led to a mining boom of this rare mineral wherever an acceptable quality and quantity of strategic mineral deposits was found.

The US government set requirements that the ore itself should carry 35 percent or more of manganese free of such impurities as phosphorus, copper and zinc. After 1941 when the US entered World War II, ensuring a steady manganese ore supply became a top priority. The US government increased purchasing manganese supplies from domestic producers to compensate for a shortage of imports, which greatly suffered due to attacks by enemy submarines on ships carrying manganese to the US.

Fort Ross’ Aho Mine

Very few people are aware that some of the manganese supplied to the US government during World War II was mined from a ridge about 5 miles from the historic Russian American Company’s Sonoma County settlement. It is also worth noting that while Russians did not mine manganese, they did introduce mining techniques in Sonoma in the 19th century.

The Aho (Drum) mine is located on the west side of a narrow canyon above Fort Ross. It was owned by Al Aho (Aho, Albert Aleck) of Cazadero during World War II. The mine was originally discovered by a Mr. Crandall of Healdsburg and was first worked from 1924 to 1926 by a lessee, C.P. Seaburg of Oakland. After this, the mine lay idle until 1940, when the government began a major manganese procurement campaign from privately operated shafts.

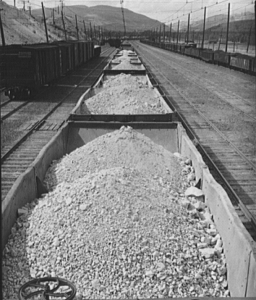

In 1942, the mine was operated by Verner Allen. Records of the manganese production around Fort Ross are scarce, but documents reveals that ore from Aho mine was shipped to the government purchase depot in Deming, New Mexico by a railroad from Healdsburg, CA.

When the mine was surveyed in 1942 by the US Geological Survey (USGS), the agency noted that Aho’s “primary ore contains 30 to 35 percent manganese, and more than 25 percent silica,” which met the government procurement standards. The report also said that the property was first developed by a series of open cuts along the ore bodies using bulldozers. Ore extracted from the mine was delivered to a loading platform some 300 feet below by a specially built chute.

The upper workings consisted of an open cut about 50 feet long by 20 feet wide, and 6 to 8 feet deep. A small adit (a horizontal passage leading into a mine) was run under the cut, so the ore could be removed through the adit. The middle workings consisted of an inclined shaft that was 20 feet deep at one end of an open cut that measured 100 by 6 feet. It had two adits. The lower workings consisted of an adit and three branches.

The total amount of ore sold to the US government by Aho Mine during World War II is unknown. Available figures claim that in 1942, three cars averaging 45 percent manganese and 17 percent silica were extracted from the mine. The weight contained in each car was not specified.

As we honor the sacrifice of millions of soldiers during Victory in Europe Day commemorations marking Nazi Germany’s surrender to Allied forces, let us also remember our local community who labored for the combined war effort. Albert Aleck Aho was born in Montana in 1911, but he spent most of his life, some five decades to be exact, calling 24190 Fort Ross Road his home.

For further reference please consult: Geologic Description of the Manganese Deposits of California By Parker D. Trask pg. 280-282 (April 1950).

-- Igor Polishchuk, Director of External Relations

The Salt of Salt Point

Collecting, growing, buying, and trading spices and seasonings has been a driving force in many economies and livelihoods throughout history - for example the East India Spice Company might come to mind. Historically, conflicts and political movements have arisen over these natural resources. One of Gandhi’s most famous strikes was a 241-mile walk protesting the British tax on salt - an essential compound used to cure many foods in the warm climate of India. Although we may think about spices and salt in a global context, the rough and rugged coastline of Sonoma County was also part of this important world history.

Walking the wildflower-abundant trail from Gerstle Cove to Stump Beach in Salt Point State Park, you might wonder how Salt Point got this title, but this is one place name that provides strong clues right in its very name.

Common table salt processed in large scale salt brines and salt collected from the ocean may have the same molecular formula--Sodium chloride (NaCl)--but they have many differentiating characteristics from one another. Salt collected naturally from ocean evaporation has many additional nutrients and minerals making its flavor and chemical properties unique to the area from where it came.

Salt was a highly prized commodity for many Native California Indian tribes in Northern California. In Tending the Wild, M. Kat Anderson writes, “Acorns were second only to salt as the most popularly traded item of the indigenous people of California.” Robert F. Heizer notes in the Handbook of North American Indians, “Pomo of the Clear Lake and upper Russian River regions, as well as Yuki and Round Valley, followed established trails across it for an important item--salt. Because of their control, or attempted control, of this economic resource, the Northeastern Pomo have also been called the Salt People.”

Salt was a highly prized commodity for many Native California Indian tribes in Northern California. In Tending the Wild, M. Kat Anderson writes, “Acorns were second only to salt as the most popularly traded item of the indigenous people of California.” Robert F. Heizer notes in the Handbook of North American Indians, “Pomo of the Clear Lake and upper Russian River regions, as well as Yuki and Round Valley, followed established trails across it for an important item--salt. Because of their control, or attempted control, of this economic resource, the Northeastern Pomo have also been called the Salt People.”

The Kashia (Kashaya) Pomo Band of Indians collected and traded salt that was gathered from the recesses in the tafoni, the unique geological feature of Salt Point's coastal rocks. Huge ocean swells splash water into the indentations, leaving salt water from the Pacific Ocean in small puddles. As the water evaporates, what’s left are sometimes quite thick layers of salt crystals.

As Kent G. Lightfoot and Otis Parrish write in California Indians and Their Environment, “When salt from seaweed was not sufficient, salt crystals could be collected from coastal pools where sea spray had evaporated or from inland deposits. Some groups made annual trips to the coast to gather salt. Salt was also traded; in fact Native Californians maintained a heavy salt traffic up and down the coast, as well as to the interior of California.”

Here in Northern California, conflict arose over salt. As Heizer writes, “Payment was usually expected both for salt that had already been collected and gathering privileges. However, many parties took the salt clandestinely without payment and, in the early nineteenth century, conflicts ensued known as the Salt Wars.”

In Robert Heizer and M.A. Wipple’s book The California Indians: A Source Book, they note, “The famed Pomo Salt Wars were caused by the unsuccessful attempt of the Potter Valley Pomo to take salt from the Stonyford people without asking permission or giving gifts for the privilege.”

It would be easy to attribute the name Salt Point to the literal ocean spray you may well find yourself sprinkled with while exploring the tafoni tide pools, but you can see that when we look a bit deeper into the place names, we are often rewarded with a rich and dare I say savory history, far more complex than expected.

--Song Hunter, Distance Learning Programs Manager